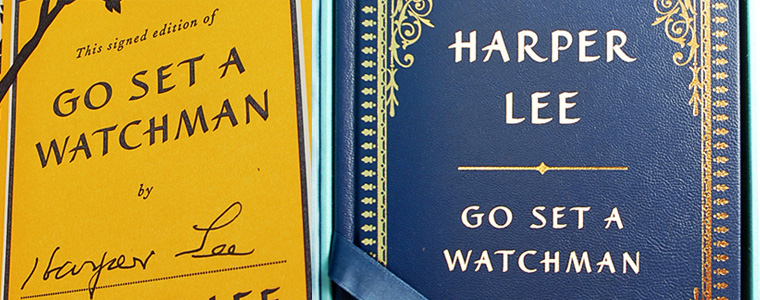

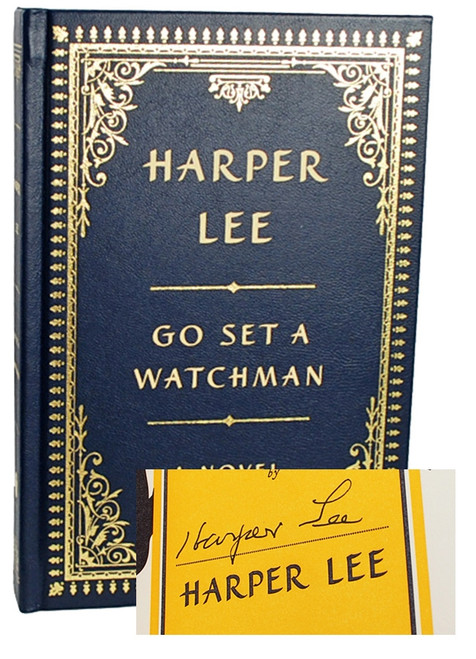

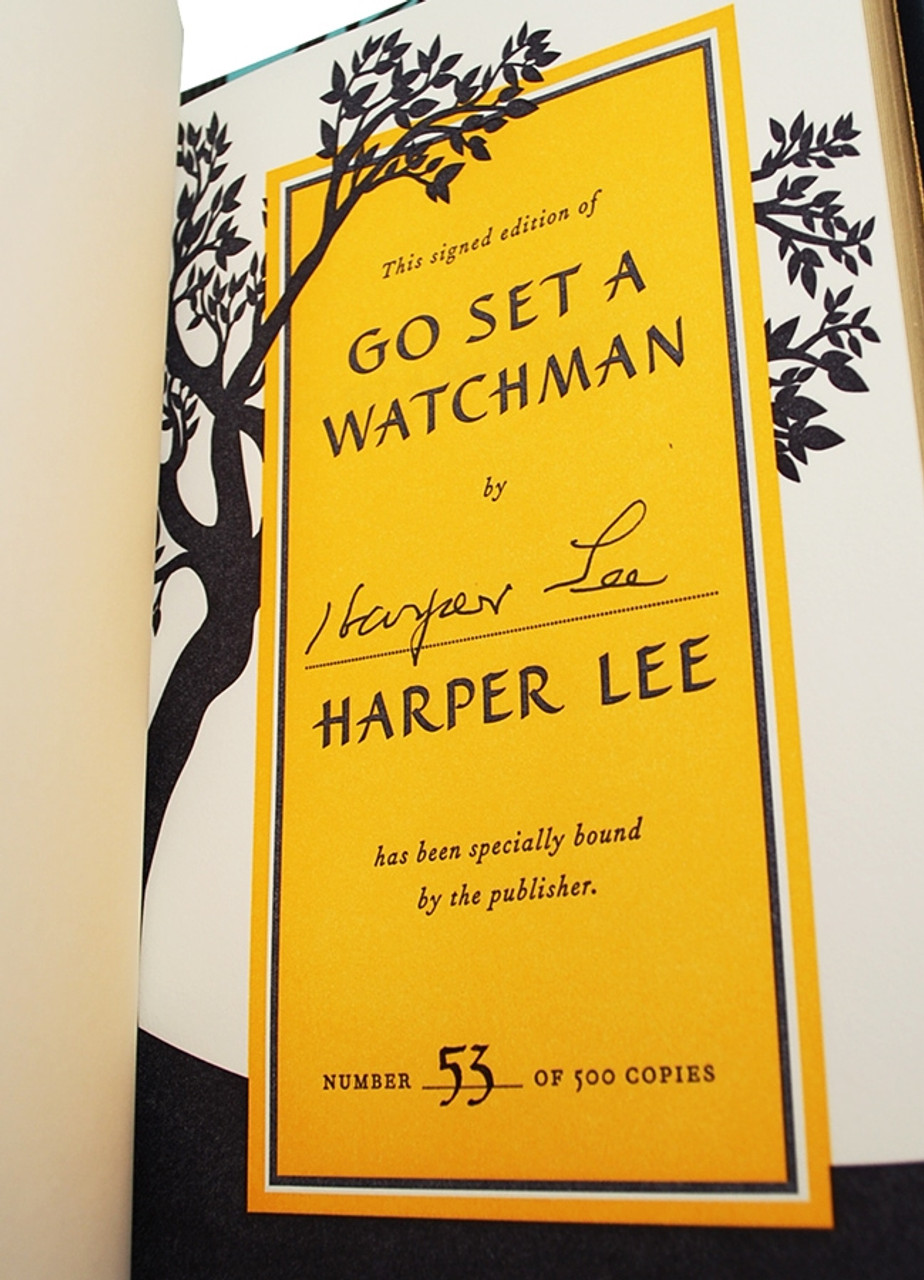

Personally signed by Harper Lee directly onto the special limitation page.

Very low number 53 of only 500 produced in this special edition.

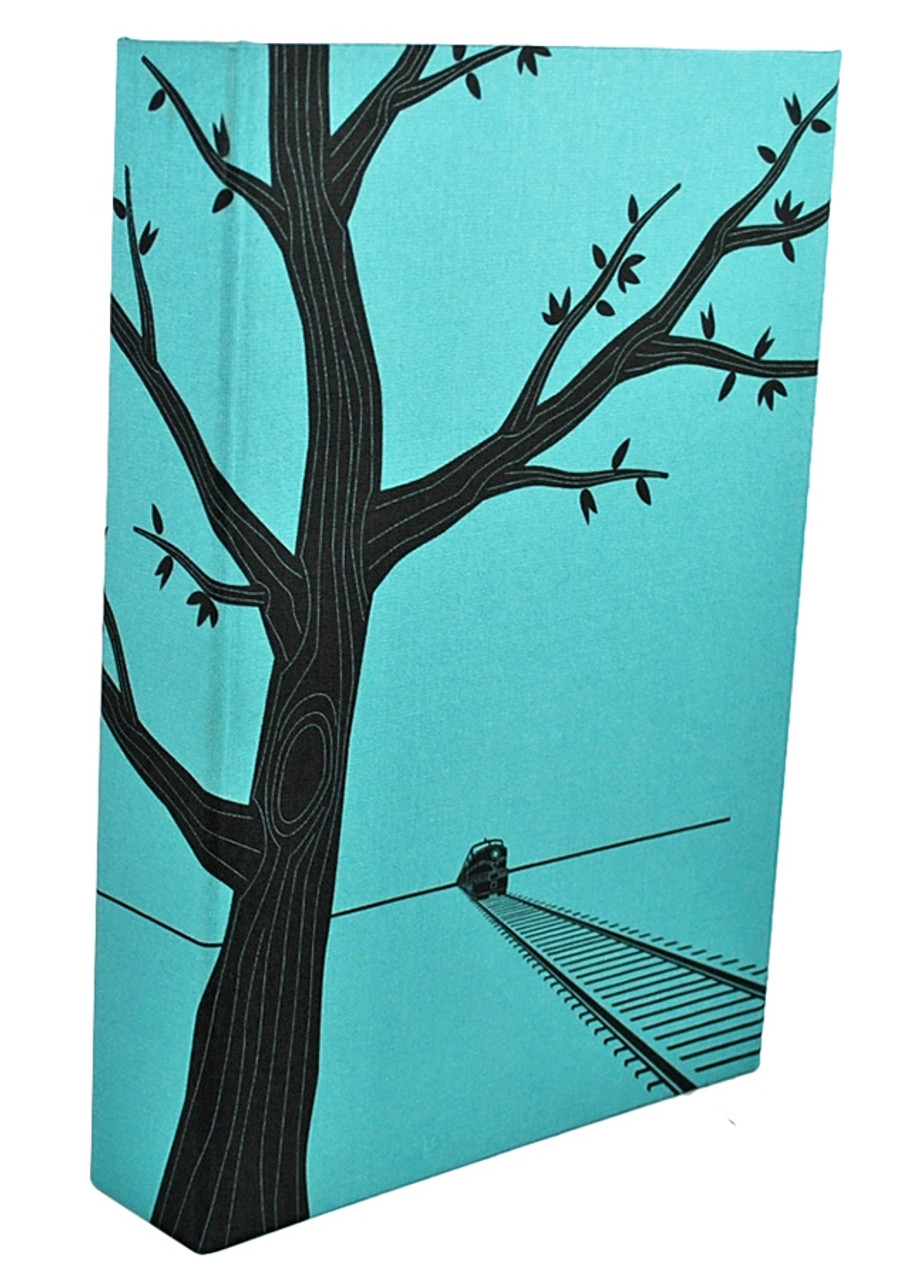

Harper Lee's landmark #1 New York Times bestselling novel, now available in a gorgeous limited edition, signed by the author and numbered.

HarperCollins Publishers 2015. Harper Lee "Go Set A Watchman" Special Collector's Edition signed by the author, and one of only 500 numbered copies. The stunning package includes a hardcover bound in leather with debossed gold foil stamping, gold gilded edges, and printed endpapers, and is enclosed in an elegant cloth box lined in velvet with magnet closure. With only 500 copies of this special edition being printed, this is certain to be a highly coveted collector's piece. Includes original shipping container from the publisher.

From Harper Lee comes a landmark new novel set two decades after her beloved Pulitzer Prize–winning masterpiece, To Kill a Mockingbird.

Maycomb, Alabama. Twenty-six-year-old Jean Louise Finch—"Scout"—returns home from New York City to visit her aging father, Atticus. Set against the backdrop of the civil rights tensions and political turmoil that were transforming the South, Jean Louise's homecoming turns bittersweet when she learns disturbing truths about her close-knit family, the town, and the people dearest to her. Memories from her childhood flood back, and her values and assumptions are thrown into doubt. Featuring many of the iconic characters from To Kill a Mockingbird, Go Set a Watchman perfectly captures a young woman, and a world, in painful yet necessary transition out of the illusions of the past—a journey that can only be guided by one's own conscience.

Written in the mid-1950s, Go Set a Watchman imparts a fuller, richer understanding and appreciation of Harper Lee. Here is an unforgettable novel of wisdom, humanity, passion, humor, and effortless precision—a profoundly affecting work of art that is both wonderfully evocative of another era and relevant to our own times. It not only confirms the enduring brilliance of To Kill a Mockingbird, but also serves as its essential companion, adding depth, context, and new meaning to an American classic.

About Harper Lee

Nelle Harper Lee (April 28, 1926 – February 19, 2016) was an American novelist best known for her 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird. It won the 1961 Pulitzer Prize and has become a classic of modern American literature. Lee has received numerous accolades and honorary degrees, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2007 which was awarded for her contribution to literature. She assisted her close friend Truman Capote in his research for the book In Cold Blood (1966). Capote was the basis for the character Dill Harris in To Kill a Mockingbird.

The plot and characters of To Kill a Mockingbird are loosely based on Lee's observations of her family and neighbors, as well as an event that occurred near her hometown in 1936 when she was 10. The novel deals with the irrationality of adult attitudes towards race and class in the Deep South of the 1930s, as depicted through the eyes of two children. It was inspired by racist attitudes in her hometown of Monroeville, Alabama. Go Set a Watchman, written in the mid 1950s, was published in July 2015 as a sequel to Mockingbird but was later confirmed to be an earlier draft of Mockingbird.

Editorial Reviews

“Harper Lee’s second novel sheds more light on our world than its predecessor did.” People

“A deftly written tale… there’s something undeniably comforting and familiar about sinking into Lee’s prose once again.” Chicago Tribune “What makes Go Set a Watchman memorable is its sophisticated and even prescient view of the long march for racial justice. Remarkably, a novel written that long ago has a lot to say about our current struggles with race and inequality.” - Washington Post

“A significant aspect of this novel is that it asks us to see Atticus now not merely as a hero, a god, but as a flesh-and-blood man with shortcomings and moral failing, enabling us to see ourselves for all our complexities and contradictions.” - Los Angeles Times

“Don’t let ‘Go Set a Watchman’ change the way you think about Atticus Finch…the hard truth is that a man such as Atticus, born barely a decade after Reconstruction to a family of Southern gentry, would have had a complicated and tortuous history with race.” - Wall Street Journal

“[Go Set a Watchman] contains the familiar pleasures of Ms. Lee’s writing- the easy, drawling rhythms, the flashes of insouciant humor, the love of anecdote.” - USA Today

“Go Set a Watchman provides valuable insight into the generous, complex mind of one of America’s most important authors.” - San Francisco Chronicle

“Go Set a Watchman’s greatest asset may be its role in sparking frank discussion about America’s woeful track record when it comes to racial equality.” - The Independent

“A coming-of-age novel in which Scout becomes her own woman…Go Set a Watchman’s voice is beguiling and distinctive, and reminiscent of Mockingbird. (It) can’t be dismissed as literary scraps from Lee’s imagination. It has too much integrity for that.”- The Guardian

“Go Set a Watchman is more complex than Harper Lee’s original classic. A satisfying novel… it is, in most respects, a new work, and a pleasure, revelation and genuine literary event.” - Denver Post

“[Go Set a Watchman is a] brilliant book that ruthlessly examines race relations" - Vanity Fair

“Go Set a Watchman’s gorgeous opening is better than we could have expected.” - Buffalo News

“[Go Set a Watchman is] filled with the evocative language, realistic dialogue and sense of place that partially explains what made Mockingbird so beloved.” - New York Post

“Atticus’ complexity makes Go Set a Watchman worth reading. With Mockingbird, Harper Lee made us question what we know and who we think we are. Go Set a Watchman continues in this noble literary tradition.” - Columbus Dispatch

“Lee’s ability with description is evident… with long sentences beautifully rendered and evoking a world long lost to history, but welcoming all the same.” - Daily Beast

“As Faulkner said, the only good stories are the ones about the human heart in conflict with itself. And that’s a pretty good summation of Go Set a Watchman.” - Vulture

“One overarching theme that many critics have zeroed in on is that there is a lot to learn from the novel, as both a writer and a reader.” - Bloomberg View

“Go Set a Watchman offers a rich and complex story… To make the novel about pinning the right label on Atticus is to miss the point.” New York Times Opinion Pages: Taking Note

“Go Set a Watchman is such an important book, perhaps the most important novel on race to come out of the white South in decades… NPR's "Code Switch"

“In this powerful newly published story about the Finch family, Lee presents a wider window into the white Southern heart, and tells us it is finally time for us all to shatter the false gods of the past and be free.”

Now that the brouhaha from the publication of Go Set a Watchman has quieted, we are left, like Maycomb's citizens, to examine society's rough judgment. In no particular order, we've heard the following: that the book is a rough first draft of Mockingbird. That it's our first taste of an adult Scout or a shockingly racist Atticus. That it's an odious money-grab on the part of its publishers, since Lee herself vowed to never write another book — and, now deaf and nearly blind in a nursing home, Lee hasn't sanctioned its publication. That the discussion of race lacks the subtlety and strength of the original, and, most important, parents who've named their children after Atticus have to rethink the whole thing.

Some of these are opinions, and some are mistaken. (Search "the Jane Austen of southern Alabama" for Harper's subsequent writing efforts — and read Mockingbird itself to see that it is entirely from the point of view of the adult Scout, looking back.) They show we have not paid a great deal of attention to Mockingbird — or to Watchman, either. Because Watchman is not a failed race novel or a rough draft of Mockingbird. It's a novel about Jean Louise becoming a woman and a sexual being.

In the novel's most vivid and brilliant chapters, the childhood Jean Louise gets her period, a teen Jean Louise unsuccessfully stuffs her (nonexistent) bra, and her adult self fumbles with the idea of marrying childhood beau Henry Clinton. That Jean Louise, just off the train and being driven home by Henry, coldly rejects his proposal at the prospect of "another shabby little affair ... la the Birmingham country club set" amid the "latest Westinghouse appliances."

Jean Louise's adult self is as cosmopolitan as her childhood self is ignorant. In this book, the dramatic crisis comes when Jean Louise's falsies wind up on a billboard honoring WWII veterans from the high school. (By way of boyfriend Henry Clinton, Atticus saves her from conviction.) In a more disturbing section, when a sixth-grade classmate gets pregnant by her father, Jean Louise, who has recently begun to menstruate, thinks she can become pregnant by a classmate who's forced a kiss on her. A brutal year passes, at the close of which she attempts suicide. She is only narrowly saved by Henry.

Slowly and deliberately Calpurnia told her the simple story. As Jean Louise listened, her year's recollection of revolting information fell into a fresh crystal design; as Calpurnia's husky voice drove out her year's accumulation of terror, Jean Louise felt life return. She breathed deeply and felt cool autumn in her throat. She heard sausages hissing in the kitchen, saw her brother's collection of sports magazines on the living room table, smelled the bittersweet odor of Calpurnia's hairdressing.

When Aunt Alexandra — whose milk glass collection, Jean Louise tells us, is a signifier of a woman who "despises men and thrives out of their presence" — throws Jean Louise a much-feared Coffee, her social gathering of the town's women, we are treated to a stunning chapter worthy of The Group (with notes of Peyton Place). Like an anthropologist, Jean Louise is the silent recipient of the idle chatter that codifies the world of Maycomb's women: "When Jerry was two months old he looked up at me and said . . . toilet training should really begin with . . . he was christened he grabbed Mr. Stone by the hair and Mr. Stone . . . wets the bed now."

Jean Louise's breasts come up again — literally — when she scandalizes the town by swimming fully clothed with Henry in the river. The gossip has Henry and Jean Louise skinny-dipping. This, like her childhood scrapes, Aunt Alexandra finds horrifying, Atticus amusing. "I hope you weren't doing the backstroke," Atticus notes wryly.

Atticus's sense of humor in that moment is much closer to the one we find in Mockingbird, but much of the hoopla over Atticus's racism may have stemmed from a misunderstanding of Mockingbird's take on race in the first place. I'm far from the first to make this observation, but for a novel that purports to be about racial tensions, most of the action in Mockingbird happens between white people. Mockingbird takes place during the boom of historically black colleges and Negro secondary schools, one in which black educators and intellectuals fanned out across the South to create an educated middle class in the midst of segregation and unchecked violence. But Calpurnia's "white" voice, it seems, is mostly learned from her proximity to white people, and her humanity is shown through her love of Scout and Jem.

The same is true of Maycomb's black community, whose humanity is evidenced mostly through their deference to white people. (Readers may note the irony in the fact that, in a book published in 1960, Maycomb's black citizens seem always to be getting up and giving the Finch children seats.) We never know how Tom feels about being stuck in a jail with only a child and lawyer between him and a lynch mob — I can't imagine heading securely off to sleep at Atticus's assurance, myself — and we'll never know how Dolphus Raymond's partner feels about the fact that he must pretend he's drunk in public to be with her. Add Lee writing about Scout breathing in "the warm bittersweet smell of clean Negro," or admiring Tom as a "black-velvet Negro, not shiny, but soft black velvet," you see that while Go Set a Watchman is controversial for some, Mockingbird was always pretty controversial for others. (I'm still waiting for the book in which a white character is introduced by his or her color and smell.)

Despite the official story, it's unlikely that Watchman is a first draft of Mockingbird. It's an entirely different book, in time period, point-of-view, and plot. (Save a few should-be- stricken scenes dropped in whole cloth from the classic.) Many reviewers have noted the oddity of Watchman's assuming readers will have such familiarity with a cast of characters we've never met before, or that Mockingbird was born of a scant two paragraphs mentioning Atticus's famous case.

Instead, Go Set a Watchman reads more like a companion book, even simultaneous draft, one in which Lee shows she's aware of a black community that attends Tuskegee and, in Uncle Jack's speeches, finds an ugly, quasi-intellectual racism closer to home. As a character, Henry Clinton gives voice to the "trash" cursorily dismissed by Atticus in Mockingbird — but as a love interest, Reader: thank God she doesn't marry him. If it's true that editor Alice Tayoff gently steered Lee into Mockingbird, I think Lee could have produced something as vibrant and interesting here, but these sections as they exist are clumsy and underworked — probably of more use to scholars and interested parties than to the devoted Lee fan.

That is not true, however, of the nearly half of the book that comprises Jean Louise's growth from Scout to a woman. Among Coffees, falsies, and the codes of southern womanhood, this book finds its truest thread. I want to see more of the post-WWII social stratum of families with their Mixmasters and matchbox houses, more of Jean Louise's life in New York, where she does not date but goes to the Artist's League to paint at night. In Aunt Alexandra's Coffee, we find an antihero that unseats Atticus. There's another novel in the ruination Jean Louise visits upon southern femininity, in what happens when she descends from the balcony below which Atticus and the townsmen talk. Mockingbird took us into the world through the eyes of a child, but Lee might have had it in her to write a classic about the education of a woman.

Lizzie Skurnick is the author of Shelf Discovery: The Teen Classics We Never Stopped Reading. She lives in Jersey City.

Reviewer: Lizzie Skurnick

Publishers Weekly

07/20/2015

Reviewed by Louisa ErmelinoThe editor who rejected Lee's first effort had the right idea. The novel the world has been waiting for is clearly the work of a novice, with poor characterization (how did the beloved Scout grow up to be such a preachy bore, even as she serves as the book's moral compass?), lengthy exposition, and ultimately not much story, unless you consider Scout thinking she's pregnant because she was French-kissed or her losing her falsies at the school dance compelling. The book opens in the 1950s with Jean Louise, a grown-up 26-year-old Scout, returning to Maycomb from New York, where she's been living as an independent woman. Jean Louise is there to see Atticus, now in his seventies and debilitated by arthritis. She arrives in a town bristling from the NAACP's actions to desegregate the schools. Her aunt Zandra, the classic Southern gentlewoman, berates Jean Louise for wearing slacks and for considering her longtime friend and Atticus protégé Henry Clinton as a potential husband—Zandra dubs him trash. But the crux of the book is that Atticus and Henry are racist, as is everyone else in Jean Louise's old life (even her childhood caretaker, Calpurnia, sees the white folks as the enemy). The presentation of the South pushing back against the dictates of the Federal government, utilizing characters from a book that was about justice prevailing in the South through the efforts of an unambiguous hero, is a worthy endeavor. Lee just doesn't do the job with any aplomb. The theme of the book is basically about not being able to go home again, as Jean Louise sums it up in her confrontation with Atticus: "there's no place for me anymore in Maycomb, and I'll never be entirely at home anywhere else." As a picture of the desegregating South, the novel is interesting but heavy-handed, with harsh language and rough sentiments: "Do you want them in our world?" Atticus asks his daughter. The temptation to publish another Lee novel was undoubtedly great, but it's a little like finding out there's no Santa Claus.

Library Journal

08/01/2015

As every reader knows, Lee's second novel, from which her iconic To Kill a Mockingbird was spun 55 years ago, has just been published by Harper with considerable excitement and some still-shifting uncertainty, as reported by the New York Times, about how the manuscript was rediscovered. Lee's original work has feisty 26-year-old Jean Louise Finch, nicknamed Scout as a child and the basis for Mockingbird's beloved heroine, returning home from New York to Maycomb Junction, AL, post-Brown v. Board of Education and encountering strongly resistant states'-rights, anti-integrationist forces that include boyfriend Henry and, significantly, her father, Atticus Finch, Mockingbird's moral center. Readers shocked by that revelation must remember that there are now two Atticus Finches; the work in hand is not a sequel but served as source material for Lee's eventual Pulitzer Prize winner, with such reworked characters a natural part of the writing and editing processes. Even if one can imagine that the seeds of the older Atticus are there in the younger Atticus—and that's possible—these are different characters and different books. More significantly, the current work stands as you-are-there documentation of a specific time and place, contextualizing both Mockingbird and the very beginnings of the civil rights movement, and for that reason alone it's invaluable and recommended reading. Mockingbird's Atticus was right for 1960, just after the Little Rock integration crisis, with his defense of a wrongly accused African American making him a moral beacon and a lesson for all. Yet for many readers, even those who love and admire Mockingbird, it also smacked of white self-congratulation, and the current book is a rawer, more authentic representation of Southern sentiment at a tumultuous time, years removed from the solidly (and safely) segregationist era of Mockingbird. If Watchman is occasionally digressive or a bit much of a lecture, it's good enough to make one wish that Lee had written a dozen works. It's also a breathtaking read that will have the reader actively engaged and arguing with every character, including Jean Louise. In the end, despite Jean Louise's powerful articulation that the court had to rule as it did, that "we [whites] deserve everything we've gotten from the NAACP," and that Negroes (as the novel says) will rise and should rise, it's unsettling and, yes, disappointing that the confrontation between Jean Louise and Atticus is ultimately an engineered effort to make her stand up for herself and stop worshipping her father. That's not quite believable, and what's right gets a little lost in states' rights, which Jean Louise herself supports. At least she doesn't run back to New York, but did she really win her argument? The ugly things she hears around her are still being said today. VERDICT Disturbing, important, and not to be compared with Mockingbird; this book is its own signal work.—Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal

Kirkus Reviews

2015-07-15

The long-awaited, much-discussed sequel that might have been a prequel—and that makes tolerably good company for its classic predecessor. It's not To Kill a Mockingbird, and it too often reads like a first draft, but Lee's story nonetheless has weight and gravity. Scout—that is, Miss Jean Louise Finch—has been living in New York for years. As the story opens, she's on the way back to Maycomb, Alabama, wearing "gray slacks, a black sleeveless blouse, white socks, and loafers," an outfit calculated to offend her prim and proper aunt. The time is pre-Kennedy; in an early sighting, Atticus Finch, square-jawed crusader for justice, is glaring at a book about Alger Hiss. But is Atticus really on the side of justice? As Scout wanders from porch to porch and parlor to parlor on both the black and white sides of the tracks, she hears stories that complicate her—and our—understanding of her father. To modern eyes, Atticus harbors racist sentiments: "Jean Louise," he says in one exchange, "Have you ever considered that you can't have a set of backward people living among people advanced in one kind of civilization and have a social Arcadia?" Though Scout is shocked by Atticus' pronouncements that African-Americans are not yet prepared to enjoy full civil rights, her father is far less a Strom Thurmond-school segregationist than an old-school conservative of evolving views, "a healthy old man with a constitutional mistrust of paternalism and government in large doses," as her uncle puts it. Perhaps the real revelation is that Scout is sometimes unpleasant and often unpleasantly confrontational, as a young person among oldsters can be. Lee, who is plainly on the side of equality, writes of class, religion, and race, but most affectingly of the clash of generations and traditions, with an Atticus tolerant and approving of Scout's reformist ways: "I certainly hoped a daughter of mine'd hold her ground for what she thinks is right—stand up to me first of all." It's not To Kill a Mockingbird, yes, but it's very much worth reading.

A Very Fine book without any flaws in a Very Fine tray-case protective box. The gilded page edges are without any marks, scratches, or blemishes. A wonderful bright clean copy without any bookplates attached or indication of any removed.

- Publisher:

- HarperCollins 2015

- Edition:

- Signed Limited Edition of 500

- Binding:

- Leather Bound

- Author:

- Harper Lee

- Title:

- Go Set A Watchman

- Signature Authenticity:

- Lifetime Guarantee of Signature Authenticity. Personally hand signed by Harper Lee directly onto the limitation page. The autograph is not a facsimile, stamp, or auto-pen.

!["Bibliomysteries" Signed Limited Edition Anthology No. 90 of 250, Tray-cased [Very Fine] "Bibliomysteries" Signed Limited Edition Anthology No. 90 of 250, Tray-cased [Very Fine]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-eohzfjch7f/images/stencil/500x659/products/2230/8625/BIBLIOMYSTERIES_6__71521.1615053227.jpg?c=1)

!["Concert For George" Deluxe Signed Limited Edition No. 2,374 of 2,500 Tray-cased [Very Fine] "Concert For George" Deluxe Signed Limited Edition No. 2,374 of 2,500 Tray-cased [Very Fine]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-eohzfjch7f/images/stencil/500x659/products/3069/15742/1280x1280__52849.1678790288.jpg?c=1)

![Charles Frazier "Cold Mountain" Signed Limited Edition #400 of only 500, Slipcased [Very Fine/Very Fine] Charles Frazier "Cold Mountain" Signed Limited Edition #400 of only 500, Slipcased [Very Fine/Very Fine]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-eohzfjch7f/images/stencil/500x659/products/1877/6510/HS440-2__45928.1601671625.jpg?c=1)

![Ania Ahlborn "Brother" Signed Limited Edition No. 90 of 500, Slipcased [Very Fine] Ania Ahlborn "Brother" Signed Limited Edition No. 90 of 500, Slipcased [Very Fine]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-eohzfjch7f/images/stencil/500x659/products/2231/8755/BROTHER_Ania_Ahlborn_2__98959.1614348479.jpg?c=1)

![Ray Bradbury "Long After Midnight" Signed Limited Edition, 95 of 100, in tray-case [Very Fine] Ray Bradbury "Long After Midnight" Signed Limited Edition, 95 of 100, in tray-case [Very Fine]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-eohzfjch7f/images/stencil/500x659/products/214/902/143-130-2__87983.1601670050.jpg?c=1)

![Ray Bradbury "Machineries of Joy" Signed Limited Edition, 95 of 100, in tray-case [Very Fine] Ray Bradbury "Machineries of Joy" Signed Limited Edition, 95 of 100, in tray-case [Very Fine]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-eohzfjch7f/images/stencil/500x659/products/217/920/143-133-2__23812.1601670057.jpg?c=1)

![Stephen King, Stewart O'Nan "Faithful" Signed Limited Edition No.146 of 350, Tray-cased [Very Fine] Stephen King, Stewart O'Nan "Faithful" Signed Limited Edition No.146 of 350, Tray-cased [Very Fine]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-eohzfjch7f/images/stencil/500x659/products/993/4188/76-810-2__86590.1601670942.jpg?c=1)

![Stephen King and Owen King "Sleeping Beauties" Signed Limited Edition No. 300 of 850 Tray-cased [Very Fine] Stephen King and Owen King "Sleeping Beauties" Signed Limited Edition No. 300 of 850 Tray-cased [Very Fine]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-eohzfjch7f/images/stencil/500x659/products/2841/24616/IMG_98-Sleeping-64__43926.1739998209.jpg?c=1)